The Best Pricing Strategy for New Products: Is It Better To Undercharge Or Overcharge New Consumer Goods? 💲

Did you know that it is more common for Australian businesses to undercharge their customers for new consumer products than overcharge them? That’s right, the majority of Australian businesses believe (either consciously or subconsciously) that the best pricing strategy for new products is to go low on the price to penetrate the market and undersell the value of a new offer – even if a new product is highly valuable to customers.

>Download Now: Free PDF How to Improve Product Pricing

Table of Contents:

II. Pricing Strategy: Organising a business for better pricing decisions

III. New Product Development Pricing Strategy: Bite-Size Yields Highest Prices

The Best Pricing Strategy for New Products: Is It Better To Undercharge Or Overcharge New Consumer Goods?

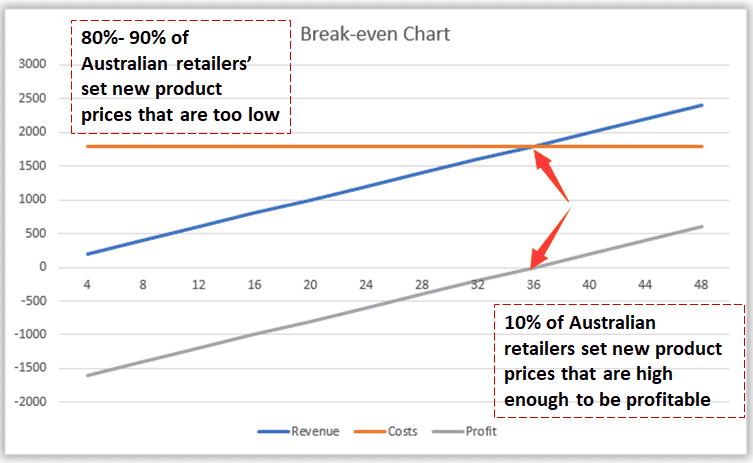

Is undercharging for new consumer products and services right? No, but it’s certainly prolific. We estimate that 80% if not 90% of Australian retailers are setting their new product prices too low. Sometimes the prices for new products are so low that they’re losing money on each sale — the opposite of the best pricing strategy for new products.

Companies like Masters, Harvey Norman, Myer, JB Hi-Fi are all included here. Even if you can’t believe it, almighty Amazon – who we all know, use Everyday Low Pricing as their best pricing strategy for new products to gain market share and share of wallet.

But what many people don’t realise about Big Scary Amazon, is that, for the first 14 years in operation, they were consistently loss-making. That’s right: they made no money. Which means following Amazon’s lead may not be the best pricing strategy for new products – unless of course like Amazon, you’re also backed by bountiful funding, wealthy investors and powerful institutions.

What’s the best pricing strategy for new products?

But if you, like me, are surprised by the extent of under-charging in Australia, you’ll be even more surprised to find that most of these businesses don’t even realise they’re excessively under-charging for new products in the first place.

That’s right; most Australian businesses are blissfully unaware that their pricing strategy is light years away from the best pricing strategy for new products – and that they’ve got a serious pricing problem.

They are undercharging customers because they are using cost plus mark up to set pricing and/or believe that flogging more stuff at low prices will lead to more revenue and more market share – when in fact, this is not necessarily the case…

You see, cost plus market not only ends up with an undercharging situation. Sometimes cost plus results in an un-competitive price point and sales volume declines or zero sales. There’s absolutely no guarantee that low prices will lead to more sales (or increase sales volume). If low prices were all people were interested in, we would:

- All be flying Tiger Airways…

- shopping at Aldi…

- All be driving Hyundai…

- Be staying at the Formula 1…

- All be eating Home Brand…

- We would all buy housewares from IKEA..

Which businesses do you think have the best pricing strategy for new products in Australia?

We estimate that only 10% of Australian businesses have any real clue about how to price according to the market and/or their customers. By this, I mean can move beyond cost plus or competitive based pricing. Then implement more expansive pricing strategies for new products. Strategies such as value-based pricing, customer-focused pricing, and dynamic pricing.

You’ve guessed it: businesses that have a long history of inelastic demand for their products tend to have the ‘best’ pricing strategy for new products. Like some major banks, telcos, supermarkets, fuel businesses and energy companies. That is if the ‘best’ is determined by their profitability and share price alone.

But do they have the ‘best’ pricing strategy for new products or are just really fortunate to have dominated a valuable industry without facing much price competition or change?

Do you think banks and telcos set fair and profitable prices?

Prices that customers are willing to pay for (not prices that customer has to pay because there’s no choice) and prices that represent value for the business and their customers (lowers their costs and increase their revenues) – the definition of the best pricing strategy for new products.

Difficult to say really because up until now most of these businesses (banks, telcos, supermarkets), have had very little competition in their respective markets compared to most other businesses in Australia.

All the businesses that do consistently set high and profitable prices for new products tend to be the top of their respective industries and for many years now. They also share a lot in common: There’s not a lot of players in these industries. Pricing structures and offers are pretty standard. Customers are restricted on choice. There’s a lot of regulatory pressure on pricing.

Which means when there is inelastic demand in Australia, prices tend to be high – which isn’t such a surprise. But what is a surprise is that not only are prices high, they are excessively high – almost to the point that new product pricing is extremely close to, if not smashing the price ceiling.

What impact will pricing through the ceiling have on leading businesses in Australia like, Telcos, Banks, and Supermarkets?

Businesses with a long history of uninterrupted inelastic demand and limited competition (fuels, cigarettes, energy, Australian supermarkets) are now under pricing pressure for the first time.

Customers want more value for their money and are demanding better customer service from their banks, telco operators and supermarkets. Excessively high prices – at this point in time – is likely to have a negative and long term impact on profitability and reputation in these respective industries. It’s possible that the ‘high price’ legacy enjoyed by so few for so long may be over.

Let’s take each of these high-priced industries one by one…

Banking

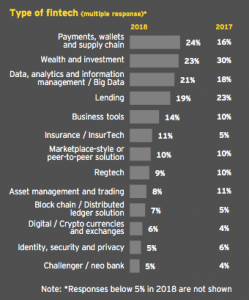

At the moment, Fintech is moving into the transactional banking space. They’re providing customer-focused solutions to improve payments and wallets (a traditionally safe and stable area for the banks for many years now).

Banks are responding by improving their IT systems and centralising transactions to make it easier for customers to make payments. However, their systems are still really quite bad. It’s going to take time and lots of training to ensure staff and customers can use these new systems.

There’s also a lot of charges and red tape. Customers are complaining they’re are not getting the advice they need from the big four banks to decrease leverage. Branch staff are not trained or capable of giving business owners wealth management and investment advice – and this is what customer really want and need.

Telcos’ pricing challenges

The telcos market is also being turned inside out at the moment. T-Mobile in the US has radically changed the global telcos market; offering simple pricing plans for multiple phone lines, including 24 monthly billing credit and phone included – no hidden charges, no data charges, more data and more video content– one of the best pricing strategies for new products in the mobile phone market.

Australian Telcos still fundamentally provide the customer with the core offer. They are still a communications services business, not a technology services business. They offer us stuff we don’t really need or want as much anymore. Like voice and SMS, limited data, limited services, slow internet, limited offer, complicated bundles, upgrade and lots of hidden charges.

Telcos have no choice but to transform their model and operations. Now T-Mobile has done it. It’s a race between who does it first now: Telstra or Optus or perhaps a techy platform-based operator will do it.

Australian Telcos is a space which is going to radically change its pricing strategy for new products. Telcos can no longer get away with charging lots of fees for every single thing – a unit based-price metric is not the best pricing strategy for new products in a transforming Telcos market.

Customers don’t like complex and confusing pricing plans and offers. They don’t want to pay hidden charges for no reason. They don’t like poor customer service whether online or offline. Furthermore, they are switching over to platform-based alternatives which make their lives easier.

>>>Read about: How CEOs make big pricing decisions

Supermarket retailing

The major supermarkets (i.e., Coles and Woolies) are also going through a major transformation. Customers are underwhelmed with their:

- warehouse-style stores

- cheap electro lighting

- limited range

- aggressive procurement style with farmers

- and row upon row of the same expensive sugar and fat products

Mainstream supermarket retailing needs to change. People are fed up with zone pricing. All incomes and demographic groups are planning to or are switching to Aldi for the bulk of their weekly shopping. People are now buying selectively from other specialist outlets for their meat, veg and even bakery goods.

Customers are now using online groceries; retailers like Harris Farm, and good quality butchers. Yes, the old-fashioned high street concept once disrupted by warehouse supermarket retailing is making a come back. And from what I can see, the major disruption in supermarket retailing is highly connected to the economic situation in Australia.

You see, traditional Coles and Woolie’s customers no longer have the buying power they once had. The majority of people in Australia are mortgaged to the hilt, with loans for everything and very little disposable income.

The median household in Australia is between $44K-$70K after tax. People may be living in $1-4M dollar homes, but they are also struggling to re-pay their mortgages, loans and buy their weekly groceries. Payments are steady, but people with mortgages and car loans have decreasing disposable income to spend on overpriced, processed groceries from Coles and Woolworths.

The Australia population is changing radically. The economics of Australia is changing. What once was the best pricing strategy for new products is no longer the best. Time to change!

>>>Read about: Underpricing: How Charging the Wrong Price Is Destroying Your Business? 🏢

Under-charging customers for new products is not the way to go either.

Good businesses are closing down every week in Australia because they are not charging customers enough for the value they are receiving. And, it seems to me, many businesses are too afraid to trial new approaches to pricing because they are afraid of how their customers would respond or simply don’t know how to do it.

Wherever, I turn to retail, fashion, electronics, B2B industrial, building materials, stationery, office equipment – you name it (even commodity and highly replicable products like pens and paper). Businesses in Australia (both big and small) are routinely undervaluing themselves. In turn, setting prices for new products that are way too low. They are educating their customers to ask for discounts and dismiss all the value they deliver.

Too much money is being left on the table. Businesses are either setting prices slightly higher or lower than their competitors OR using an incremental cost-plus pricing approach.

These are uninformed pricing practices that are costing so many businesses millions if not billions of dollars each year.

And let’s make no mistake either. This wide-scale under-charging in Australia is not down to a kind or benevolent act. All businesses want to make money – and rightly so, it’s the basis of a capitalist system.

The real issue here is that 90% of businesses in Australia don’t even realise they have a pricing problem. They are in effect blindly underselling their new product offerings and losing hard-earned revenue, profit and price positioning in the process.

Is under-charging new products a big deal?

Some people may argue at this point, that under-charging is not such a big deal. All you need to do is sell more stuff when prices are low, or if that doesn’t work, increase prices later on.

But it is a big deal…

A low price doesn’t guarantee people will buy from you on mass. People have to:

- Know of you

- Motivated to buy from you

- Informed about the offer

- Have a problem they want to solve right now

A low price for a new product doesn’t address any of these needs.

- How much will you increase prices at a later date? 2-3%?

- What are you using as your reference product?

- Across which products and categories?

- Will all price increases be the same across the board?

- What if you’re already overcharging on some items and under-charging on others?

- What is your back up plan if customers reject your prices?

When you undercharge a new product offering by just 1 per cent less than the best possible price, you’ve just given away about 8% of its potential operating profit, which means lots of hard-earned money down the drain.

Implications

It is no longer an option for big and small businesses to take an undisciplined approach to pricing anymore. Serial undercharging and overcharging is creating more harm to bottom-line profitability than good.

Profitable pricing decisions are based on an expansive rather than an incremental cost-plus approach. Cost-plus and competitive based pricing are just not good enough when you’re operating in a dynamic market and will lead to an undercharging situation.

You need to stop thinking about margin expansion just as a volume play or cost-cutting/reduction exercise. And, start thinking about how you are going to unlock the full value of your businesses and your people.

Tips to set the best prices for new products and services

- Asking customers what they would pay usually results in a price point 10-20% below what they would actually pay. This is because people are naturally biased toward obtaining a bargain or asking for discounts; which is the problem with just measuring ‘willing to pay’ when you set prices for consumer products.

- Setting an excessively low reference price might accelerate a new product’s penetration of the market. But, the resulting lower margins forgoes the future profits; a higher price would have captured once a customer base had been established.

- Setting an excessively high reference price might capture more revenue and margin in the short or even mid-term from a small group of customers. But, you’ll also isolate a large proportion of your customers who are A) not prepared to pay the high price you want and B) don’t see or understand the value that you are offering.

〉〉〉 Get Your FREE Pricing Audit 〉〉〉

Conclusion

A close look at the Australian retail and consumer market in 2019, tells me; Australian businesses (big and small) across the board need to get more scientific with their pricing. Well, if they want the best pricing strategy for new products; that drive more customer usage and more revenue and more margin that is.

When you set prices too high, you’ll lose revenue and volume. Once you set prices too low, you may not even cover your costs. When you set prices just right (i.e., known as the optimal price), however, you’ll not only delight your customers, you’ll deliver at least 10-15% earning growth (conservative estimation).

To make sustainable and profitable revenue growth (and without losing volume along the way), you need to examine the full price spectrum or range before you set a price for a new product or service.

What is the highest and the lowest prices you could charge before you set a price for a new product? Don’t know? You’ve got a pricing problem.

How can you set the best and most profitable price for a new product without losing volume or revenue? If you don’t know, you need a world class pricing manager to help you work this out.

Don’t want to do any of this? Remember there’s no reason you should be undercharging a new product. Losing your hard-earned revenue, profit and price positioning in the market. Or overcharging a new product and have people accuse you of price discrimination or price gouging.

Pricing Strategy: Organising a business for better pricing decisions

Pricing Strategy: Everyone wants to make the best pricing strategy decisions (i.e. dynamic pricing models etc); and in the heat of the moment (and sometimes without the right skills, support and information and time available), what we actually end up doing is making okay decisions and a fair few mistakes when making a business plan.

How much do these decisions cost us: i.e., in terms of our pricing professionals careers (promotion, compensation), our team (team performance, morale, job loss and redundancy) and our organisations (cost-cutting, extreme values and toxic, silo-ed culture, impact on pricing power)?

Is there some way to avoid preventable pricing mistakes to improve pricing strategy? And, do all good pricing decisions have to lead back to buying very expensive pricing software solutions?

Pricing strategy – latest research

Beshear and Gino propose an alternative solution: Alter business environments in ways that encourage teams and leaders to make better decisions. Thaler and Sunstein call this,” Choice Architecture” whereby the goal is to improve people’s decisions by carefully structuring how information and options are presented to them.

Google uses behavioural economics like “Choice Architecture” to motivate and adapt unhelpful patterns of thought. First they understand the underlying problem leading to unprofitable or unhealthy decisions. Then, they design the behavioural solution, which essentially “nudges” employees in a certain direction without, they claim, taking away their freedom to make decisions for themselves (a matter of debate, I think…).

As people, we like to think that we recognise when we make the wrong decisions. We like to think we know right from wrong in real-time. However, as many big businesses like DOW, Google, DuPont, IBM know all too well: real-time decision making is extremely difficult for us humans and at times unprofitable and destructive for the individual, team and business.

Latest research has shown, for instance, that we are basically biologically pre-wired to not even know ourselves and our weaknesses, mistakes or foibles.

We all (whether we like to admit it or not) rationalise, deny, blame and basically react in ways that push us away from the reality of our mistakes. Our ultimate comfort zone is to think we are righteous and magnanimous in most situations. However, our responses and subconscious behaviours (i.e., try thinking back to your 360 feedback from colleagues and customers for a moment if you are finding this difficult to believe) and even annual financial results can all indicate quite a different picture to the picture of reality we would hold firmly in our heads…

The human brain finds it extremely difficult to rewire itself to undo the patterns that lead to our mistakes.

If you thought learning new things was difficult, research shows that people are actually much better at learning how to make the right decision for the first time than undoing that learning and replacing it with a better way or thought pattern.

Why? You ask. Competitive plasticity research explains why our bad habits and mistakes are so difficult to break or ‘unlearn’. Most of us think of the brain as a container and learning as putting something in it. But, when we learn a “bad” habit that eventually leads to a mistake, it takes over a brain map, and each time we repeat the mistake, it claims more control of that map and prevents the use of that space for “good” habits and “preferred” decisions. And, it is this space or map in our minds that drives pricing strategy in the market (not pricing software tools).

That is why “unlearning” is often a lot harder than learning, and why finding the right people with the right mindset is critical for building high functioning teams. The fewer bad habits a person has the less unlearning needs to occur. Likewise, think very carefully about providing new recruits targeted pricing training and readiness training because it’s best to get team on the right track early, before the “bad habits” get a competitive advantage and destructive team norms set in.

〉〉〉 Get Your FREE Pricing Audit 〉〉〉

The next question is can we change and overcome our biology? Yes…

We can overcome our cognitive circuit breakers and make much better pricing options decisions in the following ways:

- Work in high functioning price management teams that coach and remind us of our strengths and goals.

- Encourage people with a performance mindset and learning agility to be the best vision of themselves and make this the norm

- Do not beat ourselves up when people are not the right fit for the new vision.

- Support compassionate leaders that know how to create positive environments in which people thrive.

- Choose to identify with ‘healthy’ organisations that value and care about people (not just profitability, hierarchy, or brand value).

- Learn and accept that we need to fail fast and safe to eventually arrive at the right decisions because this is the only way we ‘innovate’ and achieve shared organisational visions.

Click here to download your free guide on pricing strategy.

New Product Development Pricing Strategy: Bite-Size Yields Highest Prices

What is the new product development pricing strategy of FMCG companies today?

In 2017 the Office of National Statistics publicly announced that as many as 2,529 products have officially shrunk in size over the past 5 years, but are being sold for the same price. In 2020, the subject of shrinkflation is still a matter of debate in both the UK and Australia. As before, shrinkflation was restricted to mainly snack food categories. Now, however, shrinkflation has been reported to spread over to staple goods like: toilet roll, coffee, fruit juice, etc. and continue to be sold in smaller packet sizes. This is the new product development pricing strategy that food manufacturers are using.

- Consumer watchdog which? has found, for example, that some brands of toilet paper have lost up to 14% of the number of sheets per roll over two years, without any corresponding drop in price.

- Likewise, some toothpaste brands have started to sell in tubes that hold less and consequently cost more per millilitre.

- Even non-food categories, like personal care have experienced shrinkflation in Australia. With the most price increases and size reductions being appliances and personal care products. Including items like toilet rolls, nappies and tissues, and non-durable household goods like kitchen roll and washing up liquid.

Shrinkflation – when fmcg companies intentionally reduce the size or quantity of a good and keep prices the same. This is sometimes called ‘Grocery Shrink Ray’ or ‘Package Downsizing’. It is a new product development pricing strategy and an important concept in pricing because essentially it gets shoppers paying higher unit prices for less food without really noticing they are.

Shrinkflation basically means more profit for food manufacturers and supermarket retailers.

But are shoppers really getting more value for money in this new product development pricing strategy? We’re interested to find out how food manufacturers are able to pull this new product development pricing strategy off for price increase. Without most people even realising they are paying substantially more each year for essentially less and across nearly all types of food and non-food categories.

So, in this article, we’ll evaluate three different arguments for and against shrinkflation.

- That food manufacturers are reducing pack sizes without reducing the price to increase profit.

- They are shrinking pack sizes for our convenience.

- Food manufacturers are shrinking pack sizes for our health.

We’ll then discuss why food manufacturers are increasingly implementing shrinkflation. Is it because they care for consumer’s health (reducing sizes and controlling calorie intake)? Or are they just trying to cover their costs and make some profit on top? By the end of this article, you’ll learn exactly how and why food manufacturers are investing in shrinkflation as part of its new product development pricing strategy.

1. Food manufacturers are reducing pack sizes without reducing the price to increase profit.

This year, Mondelez, owner of Cadbury’s chocolate publicly announced that it remains committed to reducing chocolate bars sold in multipacks in the UK without changing the price. They blatantly came out and said about reducing pack sizes and have no intention of reducing prices.

In the same press release, Louise Stigant, UK Managing director at Mondelez International, said: “Our products have been delighting consumers for hundreds of years and we feel a strong sense of duty to preserve what makes them so special. We also recognise that we must play our part in tackling obesity and are committed to doing so without compromising on consumer choice.”

The move to cut pack sizes but not the price has been met with a backlash from some consumers and shoppers. People feel the timing is poor. As we know, many people are feeling huge financial pressure as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. For other consumers, however, this is a new topic and a phenomenon they just haven’t picked up on.

Mondelez argues that it is up to the supermarket retailers what they charge for their products.

However, they are not planning to cut their own prices. They argue they have invested in years of product innovation to give consumers more choices and flavours they enjoy.

Some critics argue that food manufacturers are reducing pack sizes by reducing the price simply to increase profitability. What’s more, they believe that they use market research to capitalise on human blind spots and weaknesses to maximise margins.

For example, food manufacturers spend millions of dollars each year trying to understand how visual cues impact shopper purchasing decisions. Notably, they have found that price and size are the two most important visual cues for shoppers.

On the matter of size, food manufacturers have learned from market research that very few shoppers examine the differences in weight for the same product over time. Rather, they find that most shoppers tend to assume pack sizes don’t change and are the same weight. What’s more, a lot of consumers are willing to pay a higher price. Especially when they believe they are getting more for their money or more value for their money.

A common practice for food manufacturers – largely stemming from this market research – therefore is to shrink the internal contents of their products gradually year on year. However, leave the external package the same size; and of course, leave the price the same.

For example, while it is common for the size of the package to stay the same after shrinkflation, often the design or picture on the package changes. Often this design change refers to the product’s ingredients. The packages now proclaiming, ‘Now with added folate’ or ‘Proudly made with 100 per cent Australian ingredients.’

This change in design but not in price is intentional. Of course, as manufacturers do not want shoppers to think they are losing out on the change in any way. Also, they certainly don’t also want people to realise that they are actually paying more for less on their snacks. Even for their staple items like bread, milk and toilet paper.

Take Cadbury’s as an example. They reduced their Mars Bars, Kit Kat, and Chunky brands over the past several years. Cadbury also decreased the number of Creme Eggs in a box. It went down to five from the original half-a-dozen and barely anyone actually noticed. That made a 16.7% increase in their gross profits for every box.

In a sense then, shrinkflation could be a food manufacturer’s new product development pricing strategy of maximising their margins from both sides of the profit equation (cost and revenue). Essentially, when they shrink the product but not the price, they are getting a price rise and decreasing costs at the same time. All the while, the shopper is blissfully unaware that their favourite products are getting smaller and they are paying more.

Is this new product development pricing strategy of FMCG companies legal?

There are regulations relating to consumers in providing information about the quantity of the serving. As well as the unit price and overall price of the product. When shrinkflation occurs the unit price of a product will become less appealing. But only a relatively small consumer in Australia notice shrinkflation, as many Australian consumers pay attention to unit prices. And, even then, they do not keep track of how unit prices are increasing year on year. They tend only to note the absolute unit price and it’s relatively to a competitive brand’s unit price. Then make a decision based on the differential.

For example, research shows that shoppers are more conscious of changes in prices and external pack size (as mentioned above) than changes in weight. What’s more, even a small increase in price can have a big effect on price-sensitive shoppers. Especially for shoppers that are already on the edge of choosing a cheaper brand based on size and price.

Shoppers, therefore, make a lot of their purchasing decisions based on two things: psychological price thresholds and unit price comparisons with like brands at a specific moment in time.

So if a price goes above a certain psychological threshold – like moving from $0.99 to $1.49 – the effect for price-sensitive shoppers is amplified and they’ll start actively comparing prices. All in all, then people will actually consciously weigh the decision of which item to buy. Rather than doing what they have always done. And this all done, largely on the spot and depending on what products they are looking at. Also, on what they are thinking about at that specific moment in time. Justification of Cialdini’s theory on price decision making.

In terms of the legal ramifications of all of this, companies have no legal requirements to run public awareness campaigns if they raise prices or change the ingredients they use or shrinkflate. Shrinkflation is undoubtedly legal but it’s debatable how ethical it is to shrink serving sizes, but not the prices and hope your customers won’t notice.

No doubt, there are some companies who do sometimes shrinkflate to increase profit margins. But, food manufacturers, like Mondelez (mentioned above) are now saying they are doing it for our health, not just to cover their costs or increase their profits. This puts a new and interesting spin on the traditional profit-making fmcg new product development pricing strategy.

Are food manufacturers now using health trends to justify higher prices for essentially reduced product? Does focusing on customer value drivers like health and convenience give food manufacturers the justification they’ve been looking for to extract more money from a customer segment already willing to pay more for their health?

Let’s look at these arguments in more detail to find out, starting with convenience.

2. Food manufacturers are shrinking pack sizes for our convenience

Though bite-size products are not new to the food industry, still major brands are continuously developing a new array of small-sized food packages. This makes it easier for people on the go. Nowadays, people are spending more time at home and the younger generations are more independent. No doubt that they are more likely to buy food for immediate consumption. Today’s generations desire convenience and portability.

Tyson, a big meat processing, for example, launched Hillshire Snacking with packs of cut-up chicken that a consumer can eat with their hands. Another example is Hormel, they created “Spam Snacks,” in resealable bags. They serve up canned meat in bite-sized pieces. Kellogg’s also made their Kellogg’s To Go pouches with slightly larger pieces of cereal. The size is comparable to a bag of chips. The company says they’re “specifically created to be eaten by hand”. Even Hershey’s made snack mixes.

A part-time student and freelance writer in Wilmington, stated, “I don’t like things that have to be assembled.” She said she picks snacks like protein bars and oranges that she can carry around in her purse.

Industry experts said that small snack packages are convenience items. And that they have one thing in common – to entice and satisfy consumers that want pre-portioned and portable snacks. Consumers don’t mind paying extra for products they see as making their lives easier.

3. Food manufacturers are shrinking pack sizes for our health

New health trends suggest that consumers are trying to minimise the amount of sugar and fat they consume, according to Euromonitor. Big companies such as Coca-Cola, Nabisco and McDonald’s have started to offer some of their products in smaller packages or servings. For example, McDonald’s is testing Oreo Thins and Coca-Cola has created their mini cans soda. The SuperSize option in Australia has gone completely and in its place are the smallest replacements ever to McDonald’s, especially for sugary drinks. However, the unit price is the same if not more expensive for these sugary drinks than ever before.

The motivation behind the reduction in size for snacks, but not the price is that they believe that, eating smaller snacks is less detrimental to the diet. Paying a higher price is like a reminder to us about our health.

Let’s take Oreo, for instance. A Mini Oreo is about one inch in diameter and the original cookie measures about 1.75 inches across. According to Nabisco, one regular Oreo is equivalent to five Mini Oreos. This is what gives consumers the understanding that mini cookies are “lighter” or are good for their diets.

The vice president for snacks at Pepperidge Farm foresees that the market for these small packages would undoubtedly double because they help consumers eat less without having to count their calorie intake.

It seems like there’s a race in the food industries to offer less. As people do seem prepared to pay more for less when its about health and convenience.

Hartman Group reported that 29% of Americans don’t mind paying extra for 100-calorie packages. Some even think that 100 calories are too much for other diet-conscious customers. For example, Hershey’s created a 60-calorie chocolate bar and Jell-O also made 60-calorie pudding.

The assumption from food manufacturers now then is people think something is healthier when they see low-calorie food packages. However, Lisa Young, author of “The Portion Teller Plan,” a book on portion control, says, “A single portion of junk food is better than a large portion of junk food, but it’s not better than an apple, a peach or a vegetable.”

One shopper in Midtown Manhattan that bought Chips Ahoy said, “They’re pretty expensive, but they’re worth it. It’s individually packed for the amount I need, so I don’t go overboard.” She said that the small Chips Ahoy does the portion control for her. Further saying that she considered the extra money she pays for 100-calorie packs a kind of convenience surcharge.

Discussion: Controversy on the convenience and health reasons for the new product development pricing strategy

Does this new focus on health and convenience mean we’ll see a sugar and food tax added on our food bills – for our convenience and health, of course? What’s more, will people actually be out in the streets campaigning for food tax to be added?

If that’s the case, new consumer insights generated by food manufacturers like Hershey and Mondelez blast traditional fmcg manufacturers assumptions about consumers out the water. Many fmcg manufacturers for years believed it was not possible to raise prices straight out for their products. For many years now, most fmcg firms viewed consumers and shoppers as price-sensitive and themselves (i.e., what they were selling) as a commodity.

However, it looks like the real reason food manufacturers couldn’t raise prices (or only justified price increase using cost increases) in the past was because they didn’t have a customer or consumer-focused fmcg pricing strategy. When you sell junk food as healthy, it stops being a commodity and starts being a special treat; and fmcg firms can illegitimately increase prices.

What’s the real cost of food manufacturers ignoring consumer trends and not developing a consumer-focused fmcg pricing strategy? In effect, trillions of dollars each year.

FMCG sales make up for more than half of all consumer spending. Meaning, that more than 50% of what consumers spend goes on FMCG goods. According to BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis), the amount of money going to FMCG organisations was $13 trillion in the second quarter of 2020.

Hershey’s research reveals that some people snack “10 times a day.”

“People are snacking more and more, sometimes instead of meals, sometimes with meals, and sometimes in between meals,” said Marcel Nahm, head of North American snacks, Hershey’s.

According to Statista, in 2020, snacking is a growing $100+ billion business in the United States. Another report acknowledges the increasing snack frequency of consumers. It states 70% of adults in the US snack 2+ times daily and 5% are doing so once a day. The rest of the percentage is for those snacking 4+ times a day.

How about you, when was the last time you had a snack? Most probably, just a few hours ago. The latest is a day ago, I guess.

People no longer strictly eat during normal meal times especially those with busy lifestyles. They nibble or snack when they get hungry. Sometimes skipping regular meals altogether. Thus, with the changing of people’s eating habits, food businesses are thinking of how they can create snacks out of normal food. Meaning, everything like grilled chicken, cereal, chocolate, peanut butter and even Spam. That’s how they came up with the basis of shrinking food packages – they want to deliver maximum convenience to people. So that they can eat whenever and wherever they want. Food in small packages or bite-size snacks come in handy.

Implications

Mondelez is an exceptional case in this debate because they are the first fmcg to admit to increasing revenues based on diet trends. Most fmcgs just say they are reducing pack size and keeping prices the same or increasing prices because of increasing operational or commodity costs. They don’t tend to admit to making profitable revenue growth from price increases or consumer trends. Mondelez, therefore are a landmark case. What does this mean?

- It looks like more fmcg will be using consumer data on key trends to justify price increases.

- Mondelez is ahead of the curve in terms of its pricing and consumer insights and obviously have a sophisticated customer-focused pricing system worked out and operating to justify their pricing and strategy.

- It’s only a matter of time before other FMCG follow and do the same.

- It looks like there are going to be a number of integrated transformation occurring in FMCG soon.

〉〉〉 Get Your FREE Pricing Audit 〉〉〉

Conclusion

Snacking is the no.1 growth area for fmcg businesses today. It’s also a highly profitable area for both food manufacturers and supermarket retailers. Whether ‘healthy snacking’ is really better for people’s health is debatable. Obesity levels are high and growing. The lockdown hasn’t helped our waistlines at all. In fact, bite-size snacks could in a way encourage unhealthier eating habits – not better.

The fmcg companies that utilise evidence-based consumer and pricing insights to create and capture value evidently appear to be in the box seat. They’ll have mind share and market share. What’s more, there’ll be able to drive profitability by giving shoppers what they want – or what they think is good for them. What’s more, they’ll no longer have to shy away from awkward price rise situations with either their retail customers or the end consumers because both will willingly pay more for less if the agenda behind the price rise is in line with the right trends.

For a comprehensive view and marketing research on integrating a high-performing capability team in your company,

Download a complimentary whitepaper on How To Maximise Margins.

Are you a business in need of help to align your pricing strategy, people and operations to deliver an immediate impact on profit?

If so, please call (+61) 2 9000 1115.

You can also email us at team@taylorwells.com.au if you have any further questions.

Make your pricing world-class!

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Categories

- marketing strategy (26)

- Organisational Design (14)

- Podcast (114)

- Pricing Capability (87)

- Pricing Career Advice (10)

- Pricing Recruitment (19)

- Pricing Strategy (289)

- Pricing Team Skills (13)

- Pricing Teams & Culture (24)

- Pricing Transformation (47)

- Revenue Model (25)

- Sales Effectiveness (27)

- Talent Management (7)

- Technical Pricing Skills (35)